The beloved – The Mashooq – has always been a source of disruption. From folk tales of Mirza and Heer to Sohni and Mahiwal, history is filled with stories of lovers losing themselves in pursuit of their beloved.

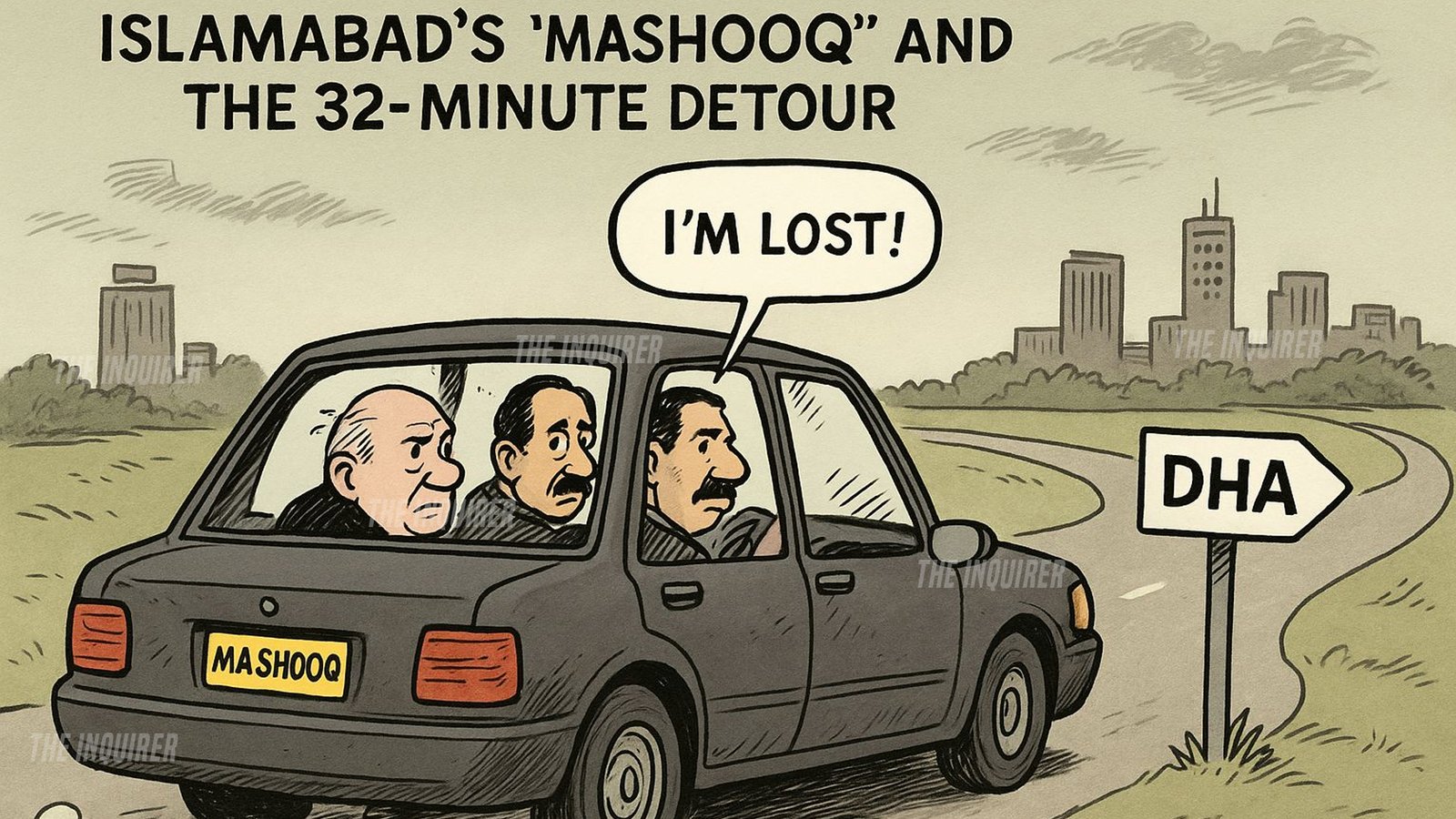

Last week, Islamabad witnessed its own version of such a tale, when the President of Pakistan, Asif Ali Zardari, and Interior Minister Mohsin Naqvi lost their way in the capital, all because of a man named Mashooq.

The incident occurred last Friday, when the president and the interior minister set out for a private visit to DHA. Protocol required the Presidency staff and Islamabad Traffic Police to identify and secure the location in advance.

Under normal circumstances, VIP convoys travel directly and smoothly to their destinations. But this time, the escort vehicle was driven by Inspector Mashooq of the Islamabad Traffic Police, a veteran officer nearing retirement.

His navigation system failed mid-route, and with it, his sense of direction. What should have been a straightforward journey turned into a 32-minute detour, leaving the president and the interior minister delayed and the entire police system alarmed.

Agencies scrambled to trace the route as news spread that the head of state and his interior minister had effectively gone “missing” en route to their appointment. Eventually, the destination was located, and the dignitaries arrived safely.

The episode, however, did not end there. That very evening, Islamabad’s Chief Traffic Officer, Zeeshan Haider, was removed from his position. His sudden removal raised questions within the police force and among observers.

If the navigation failure occurred in “Mashooq’s” vehicle, why was the CTO singled out for punishment? Why were the Presidency staff who were also in the vehicle not held accountable?

Islamabad’s traffic management system, like any organised network, is not the responsibility of one man alone. From senior superintendents to field officers, an entire chain of command is in place.

Yet, in this case, only one official was made the scapegoat.

Within twenty-four hours, however, a quiet reversal began. Zeeshan Haider, who also held charge as SP Security, was reinstated in that capacity, while Captain Hamza was appointed as the new CTO.

The reshuffle was presented as routine, but it highlighted how quickly responsibility is shifted when VIP convoys face disruption.

For the incoming CTO, the challenge is clear: maintain the precedent set by previous officers who personally managed traffic on the roads to prevent gridlocks and ensure smooth movement for both the public and VIP delegations.

The affair underscores a deeper issue within Islamabad’s policing culture. Negligence can occur at any level, but accountability must be shared fairly.

Punishing juniors while sparing seniors erodes both morale and credibility. In this case, along with Mashooq, Presidency staff members were also in the vehicle and equally unable to guide the convoy.

Yet no questions were asked of them. Instead, one officer bore the entire burden.

Islamabad’s “mashooq” may have been only a name, but the chaos it triggered revealed fault lines in a system meant to operate seamlessly.

For the future, the lesson is straightforward: when mistakes happen, responsibility should not be shifted onto a single scapegoat.

In matters of governance and policing, just as in the age-old tales of lovers and beloveds, losing the way has consequences far beyond the journey itself.